Ward-Thomas Museum

Little Steel Strike in Niles, Ohio — 1937

Ward — Thomas

Museum

Home of the Niles Historical Society

503 Brown Street Niles, Ohio 44446

Click here to become a Niles Historical Society Member or to renew your membership

Click on any photograph to view a larger image, click on image again to zoom into photograph.

|

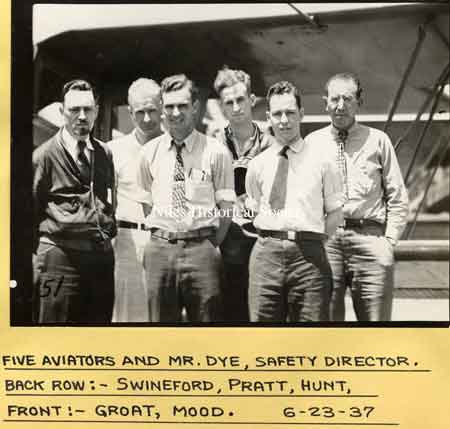

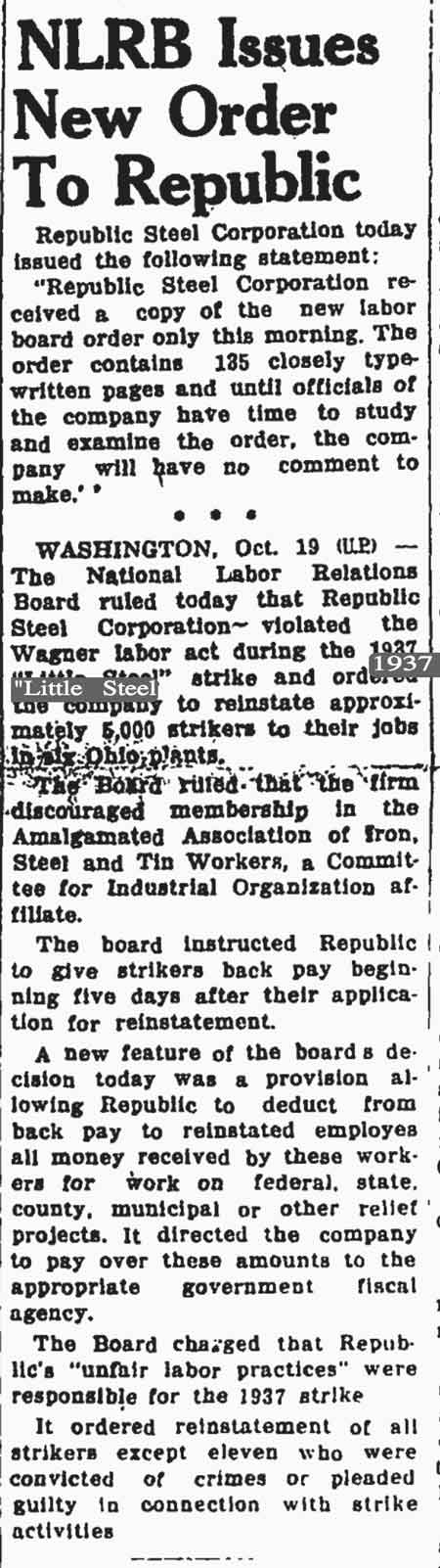

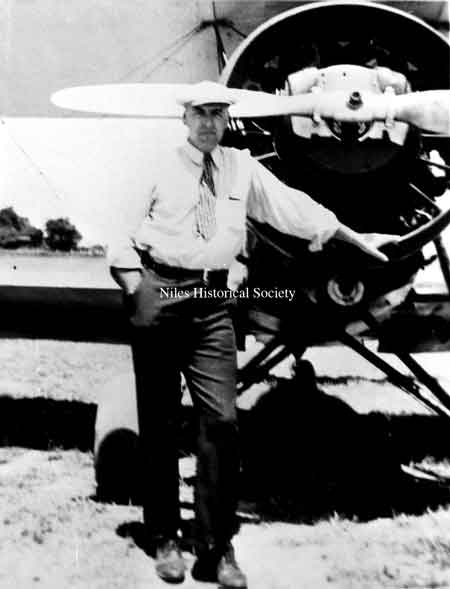

Pilots that flew food planes during the 1937 strike. L to R: B.T. Dyc, Safety Director Republic Steel; Ben I. Swineford, pilot; Frank Groat, pilot; L. Croft, pilot; P. Mood, pilot; J. W. Hunt, pilot Lic. No. 761045. PO1.1044 Planes waiting to be loaded for the food drop at the Niles Republic Steel plant during the 1937 strike. PO1.1037 Food plane and pilot Frank Groat. PO1.1042 Food storage tent and loading station in Ashland Airport. PO1.1038 Loading 30# food bags to be dropped at Republic Steel in Niles in 1937. PO1.1035 |

Little

Steel Strike in Niles, Ohio — 1937. Republic Steel president Tom M. Girdler had created a Maginot Line with other “little” steel companies—Bethlehem, Inland, National, Youngstown Sheet and Tube—to stave off trade union formation by the newly formed Steel Workers Organizing Committee, a branch of the Congress of Industrial Organizations. Big Steel, as the industrial Goliath, United States Steel, was known, recently had agreed to recognize the union. To Girdler, this was nothing less than betrayal and capitulation. He was ready for war. On May 20, he shut down Republic’s Massillon mill. Six days later, the SWOC ordered a strike against Republic and Sheet and Tube operations. Strikers formed a heavily armed picket line around the plants, blocking people and supplies from entering and loyal employees from exiting. After hearing that 2,600 employees were holed up with almost no food or supplies in the Niles and nearby Warren plants, Girdler hatched a scheme to send them sustenance. “We were going to fly it!” he wrote in his autobiography, Boot Straps. “Airplanes were the only answer.” The first aircraft to be made available,

a Waco biplane, belonged to a company employee. Bread, ham, beans,

and canned salmon were packed into padded sacks. On the first

attempt, two sacks landed outside the Niles plant fence and fell

into the hands of union pickets. But a second drop successfully

landed 10 sacks, and Girdler’s employees were soon eating. Source:https://www.airspacemag.com/history-of-flight/oldies-amp-oddities-the-little-steel-strike-airlift-41977502/ |

|

| |

||

| Strike

- loading food to be dropped at Niles Republic Steel Plant. Each

bag contained 30 # of food. May 1937, the Steel Worker's Organizing

Committee struck the "little" steel companies, including

Republic Steel plant in Niles. Large numbers of workers remained

on the job. Unable to supply themselves with food and other necessities,

Republic resorted to an air delivery system. They flew low to

drop their loads into nets set up in the parking lots. Strikers

fired at planes as they came in to make a food drop. PO1.1036

|

||

| |

||

|

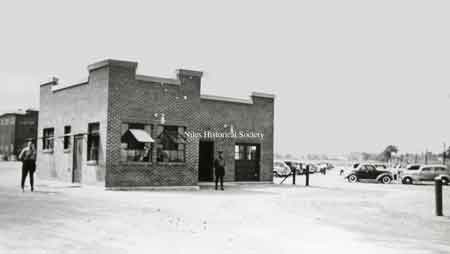

Guard house and gate of Republic Steel. PO1.1045 |

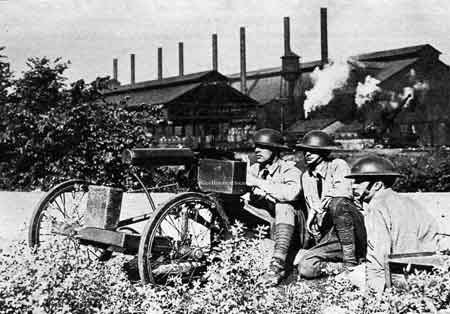

National Guard at Republic Steel with machine gun setup. | |

| |

||

|

Aerial View of Republic Steel

Plant in Niles. |

Aerial view of Republic Steel Plant in Niles, Ohio showing food drop area. PO1.1046 |

|

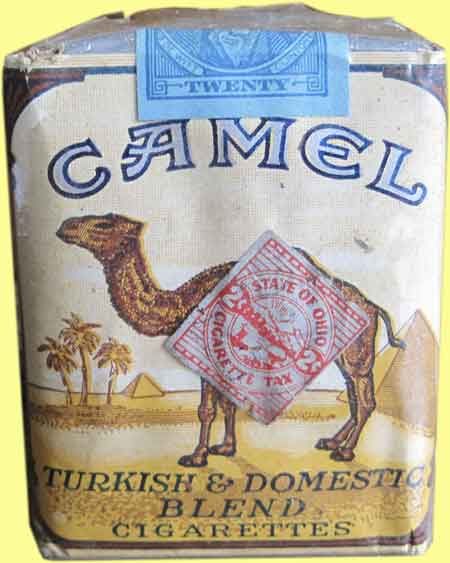

| “I’d Walk a Mile for a Camel” This pack of “Camel” cigarettes has a real story behind it. It has been unopened for years. It was dropped from an airplane when the strike was on at the Republic Steel plant in Niles, Ohio in 1937. Large numbers of Republic workers refused to leave the plant during the strike and remained at work. Unable to supply them with food and necessities, the company resorted to an air-delivery system. Planes could not land at the Niles plant so an “air drop” system began. This pack of cigarettes, however missed its mark and fell outside the compound. It was picked up by a little boy named George John and he brought it home. George John has been a vital volunteer for The Niles Historical Society especially with his carpentry skills and knowledge of plants and trees in working on the many buildings at the Ward-Thomas Museum and maintaining the grounds. George NEVER smoked, but loves to save things, so he recently donated it to the museum. Well, it definitely carries Niles history with it and is over 73 years old now. The strike was marked by bitterness and violence

and the Ohio Governor, Martin Davey, put Mahoning and

Trumbull counties under martial law. Armed troops patrolled

Niles, Warren and Youngstown. A “back-to-work” movement

began, successfully breaking the strike. |

||

| |

||

Little

Steel did not accept unionization until 1941. |

Food plane and pilot. PO1.1040 Food plane and pilot. PO1.1043 Republic Steel fleet of food planes at Ashland Airport. PO1.1039

|

|

|

|

||